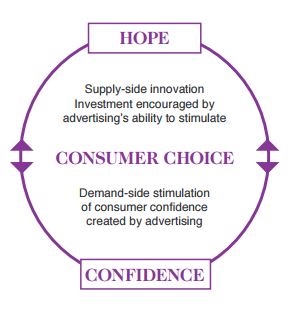

Boyfield’s paper offers vivid evidence of what happens when that virtuous circle is slowed, and the freedom to ‘aggressively stimulate’ is stifled. He uses three powerful case histories as control examples of markets where the corporate ‘hope’ that advertising provides is restricted by regulation: firstly, the optician’s market; then sanitary protection products (sanpro); and finally, and most gloriously, in the command and control economy of pre-glasnost Poland. He shows that, without the hope of advertising, markets stagnate, innovation dries up, and choice becomes stifled.

Looking back now through the lens of the Specsavers Grand Prix IPA Effectiveness paper, who can doubt that choice, service and value have leapt forward since the removal of those restrictions?

Looking back now through the lens of the wonderful ‘Like a Girl’ Cannes winner for Always, who can doubt that teenage girls are better informed since they were allowed to see advertising on the choices available to them?

Looking back now through the lens of the growth of the consumer economy in Poland, who can think it was better for people to wait in queues for sad, half-empty supermarkets to open just to satisfy abstract concepts of market control?

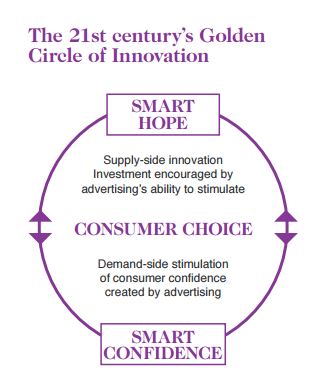

So, if Boyfield proves what can go wrong when the oxygen of advertising is cut – and the last 25 years since his paper was published proves what can happen when oxygen is pumped back into the system – can we now go one step further and prove the benefit more positively; i.e. if we increase advertising, do we get even more choice?

I would argue ‘yes we can’ – if we, again, use our common sense and look around us. Consider your local Starbucks and its orders for ‘skinny, tall decaffs’, ‘caramel Frappuccinos’ and even the odd ‘chai latte’. Apparently, we enjoy five times as much choice in our average supermarkets than we did in 1975, according to the US Food Marketing Institute. That choice extends into every aspect of my life – from the car I choose and the fashion choices I make, and where I make them, to my entertainment. If I want, I can switch and compare nearly anything I choose, to my heart’s or my pocket’s content. We don’t seem to be suffering from a lack of choice; that is for certain. If anything, the suggestion nowadays is that we are deemed to suffer from too much choice.

I ask myself, ‘is it by chance that this super-abundance has grown in line with advertising’s own dynamic growth both in quantity and variety?’. I don’t think so. I would argue that this rise of media choice has actually provided even greater hope for today’s supply-side investor.

Nick is an award-winning brand and advertising specialist with over 30 years’ experience. He joined Bartle Bogle Hegarty in 1986. He has worked on new product launches, such as Häagen-Dazs and Boddingtons, as well as already famous global brands such as Johnnie Walker and Unilever’s cornerstone laundry brand ‘Dirt is Good’.

Nick is an award-winning brand and advertising specialist with over 30 years’ experience. He joined Bartle Bogle Hegarty in 1986. He has worked on new product launches, such as Häagen-Dazs and Boddingtons, as well as already famous global brands such as Johnnie Walker and Unilever’s cornerstone laundry brand ‘Dirt is Good’.